This post is for paying subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.

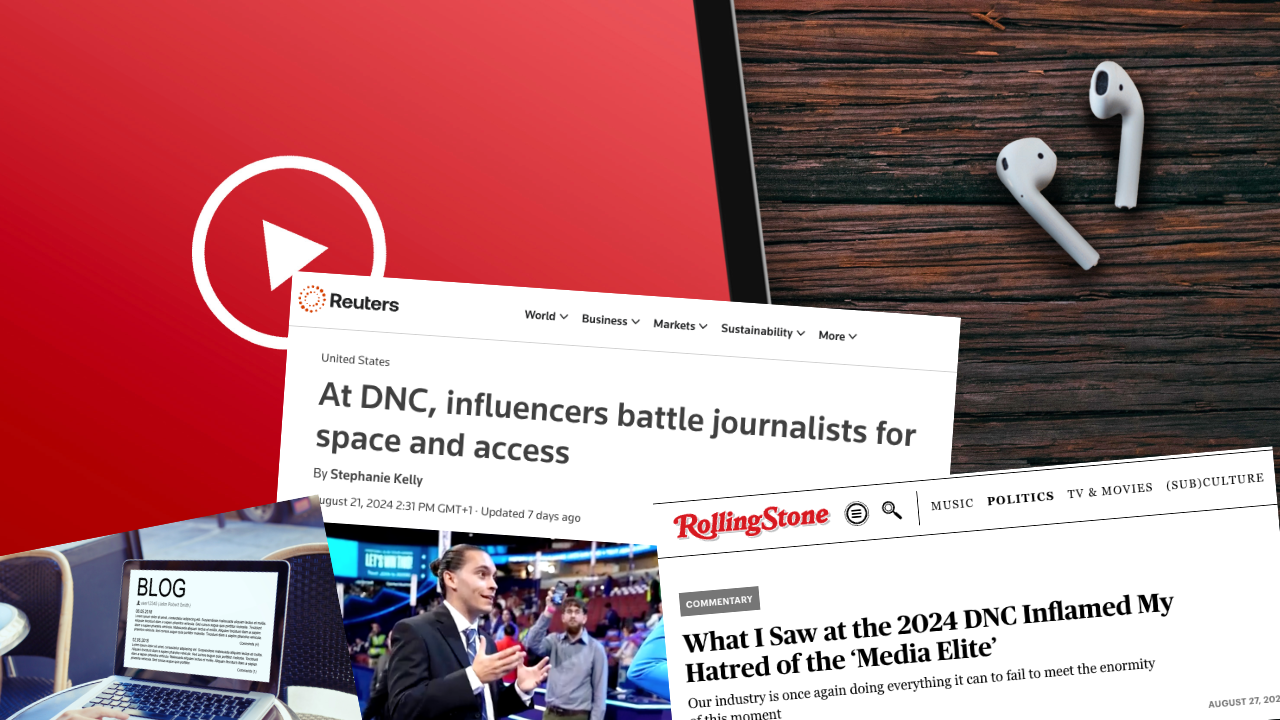

Having lived through the 'blogging is a hobby'-era, this journalists vs creators "debate" feels like nostalgia all over again...

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.

Already a member? Sign in