My internet feed is full of misinformation. Not about the US Election but in reaction to Lily Allen’s recent tweet about her feet.

For those of you who have left Musk's Twitter, here's what Lily said:

In response, there‘s been a slew of whataboutery posts, as well as articles that misunderstand how record deals and streaming works (even from places like Variety), making proclamations about the broken state of the music business. Don’t get me wrong, it is in a right mess but it’s far more complex than it seems.

Is the British popstar earning more from "feet pics" on OnlyF*ns than from her millions of monthly Spotify listeners? Well yes, but probably not for the reason you think...

Spoiler: At $10 a month subscription from 1000 subscribers, it is unlikely Allen is earning £30,000 a month - as some have suggested by confusing how music royalties work - from sharing her feeties (is that what a selfie of your feet is called?).

TL;DR? It is much more likely she's still in debt to her record label and maybe her publisher too, so does not yet get paid from her Spotify streams. Or if she is in profit and does get royalties, her slice of the major label pie will be teeny tiny.

Somewhere Only We Toe

Amidst the dismissive misogyny, there are a lot of assumptions about Allen's income from her music based on misunderstanding how the music business works.

Engagement-bait accounts like PopCrave posted this, which is symptomatic of the reaction:

Lily responded:

"this is incredibly misleading, but i’m not smart enough to explain how i make a tiny percentage of what is quoted here. you’ll just have to trust me that neoliberal capitalism doesn’t care about artists being paid for their work."

Am I smart enough? Maybe not but given a few posts have gotten up my nose about this, I'll give fact checking a go and try explaining how the music business actually operates.

Many of the responses to Allen feature common misconceptions about how artists make money.

Before I begin, I need to make clear I don’t know precisely what deal Lily Allen signed, so some of this will be making assumptions based on industry averages and draw on some of my over decades experience as an artist manager and independent label founder. I’m also going to over simplify some of the complexity to try not to make this too confusing for anyone outside of the biz as the way the money flows can quickly feel like an ouroboros, where a serpent eats its own tail, then coughs it back up.

Stop Calling Musicians "Creators"

Before we begin deconstructing how album deals work, you need to know that comparing OF subscriptions to music streaming revenue is like comparing oceans to oranges (or maybe, streams to streams of revenue).

The music business and the creator economy are wildly different. For instance, Lily Allen signed her record deal in the Myspace-era, before Spotify existed, and she got a lot of money upfront (£300,000 according to something she reportedly said in 2012 in this interview with the Evening Standard). Getting money in lieu of income is very rare for video makers, podcasters, bloggers, sole sharers, and other types of "creators" where ongoing support from advertising and fans is the norm.

These days, plenty of people want to call musicians "content creators" but it feels dismissive because music is not "content". It's songs that reconfigure your soul, it's era-defining albums, it's life-changing concerts, it’s 90 minute drone pieces, and 1.316 second Napalm Death songs.

Conflating "music" with "content" benefits vulture capitalists that often seek to dehumanise and devalue music, converting it into data then slinging it in with the digital gloop of everything and anything online from a social post to an encyclopaedia or 20 part investigative documentary or a 3 second meme video.

(Don’t worry, I’m getting to how the music business works in a minute)

Creators tend to own and market their own content, selling it directly to their fans. Whereas in music, there is an investment model involved in owning songs and the copyrights of entire artist catalogues, so that the music can be licensed, manufactured, and sold.

So even if an artist is selling direct to a fan, they may have had to buy stock of their own record from the copyright owner (their label) (or their mates dad who paid for the recording and pressed up some CDs) in order to sell it directly on the merch desk or through Bandcamp. And if they release or perform a cover, a chunk of that money goes to the songwriter.

Record labels put their resources around a release, lean on their powerful networks of connections, cover marketing costs, and ensure the music is manufactured and distributed. With 120,000 songs released every day, cutting through the noise is harder than ever, which means marketing savvy and advertising spend is crucial. As is getting paid, because music is now consumed on a range of platforms and in a multitude of formats, across different countries with different laws/currencies/business models, all of which requires infrastructure to ensure the music is available, that the store / platform seriously considers it to be featured, and that the money is collected, then paid to the right people.

Even if the person owning the copyright is not a label but the artist themselves, self-releasing to their fans, licensing it to platforms and manufacturing stock, there's a huge investment required before you break even. Once they've made a record, acts who want to make an impact with their release usually need to pay a small village of specialists to help promote a release and will definitely need to invest weeks of their life into the process. Their digital distributor will also charge a fee or take a percentage. As will stores selling their product.

("creators" also have costs and time investment to make YouTube video essays, need gear & software to make a podcast, some spend money to market a newsletter, others take out ads to promote their subscription service, etc)

"I'm on the right track, yeah, I'm on to a winner"

Lily Allen, 'The Fear'

Allen's Advances

In short, the reason Lily Allen earns more from photos featuring her naked toes than from music streaming is that she likely hasn’t yet recouped the advance she received when signing her record and publishing deals. And even if her records have become profitable, a major label deal often means she only gets a very small royalty, minus a management commission.

Let’s break this down a little more, starting with the record deal:

An advance is money artists receive upfront, before selling or streaming any records. But in addition to this initial payment, a running tab of costs starts accumulating from day one. These costs focus on making and marketing the record, such as recording, producing videos, advertising, tour support (this happens less and less nowadays but it’s the underwriting the costs of touring, covering the session musicians, crew, rehearsals, stage production, travel, etc and costs can be £1000s more than the fee for a show. These costs can be especially high for support slots which often pay £150-500 and promo events like in stores, radio sessions, and tv appearances - with the added costs of stylists, etc), and more.

Not all costs are recoupable. For instance, the label’s day-to-day operations - such as salaries for label staff, office rent, and utilities - are generally not charged to the artist. Fees paid to third-party distributors or retailers to handle physical or digital product aren’t directly billed to the artist, though they may reduce the artist’s revenue indirectly if deducted from gross revenue before royalties are calculated. In some contracts, costs for creating and distributing promotional copies for press may be covered by the label, though this varies, and in certain deals, a portion of these promotional expenses might still be recoupable.

Once the release starts generating income, the artist begins paying back this ‘debt’ through their share of revenue.

Here’s the kicker: even when streaming revenue starts coming in, only a small portion may go toward paying down this advance and the costs. For typical major label deals, as little as 18% of record sales and streaming revenue goes toward repaying the advance (i.e. 18p of every pound generated goes to the debt), while the remaining 82% goes to the label to cover the non-recoupable expenses and their operating costs. This means Allen's payback progress is slow, even with millions of CD sales and monthly streams. Only once she reaches recoupment and the project goes into profit will regular royalties begin to flow.

You could think of a record deal as a high risk pay day loan, that few ever payback.

Not all deals are structured like this, for instance Drowned in Sound‘s label embraces the more ethical, artist-friendly profit-split structure, following in the foot steps of independents like Factory (Joy Division, Happy Mondays, OMD, etc) and Dischord (Fugazi, Q and Not U, Minor Threat, etc). The upfront advances for these types of deals are usually much smaller as the risk is shared but the benefit from success is much higher for the artist. Often the advance is to pay for the recording and the label then licenses that album(s), rather than owning all music created during the deal period, as some recording contracts have clauses for.

There are also some acts signed to 360° deals, which involves the label getting a share of not just streaming but also merch, live, brand deals, etc. I snarkily called my management company CCCLX, which is 360 in Roman numerals, as it was originally set up to manage Ed Harcourt and help him self release the Back Into the Woods album.

If Lily had signed a 360° deal, Warner Music might be getting 82% of her OF money.

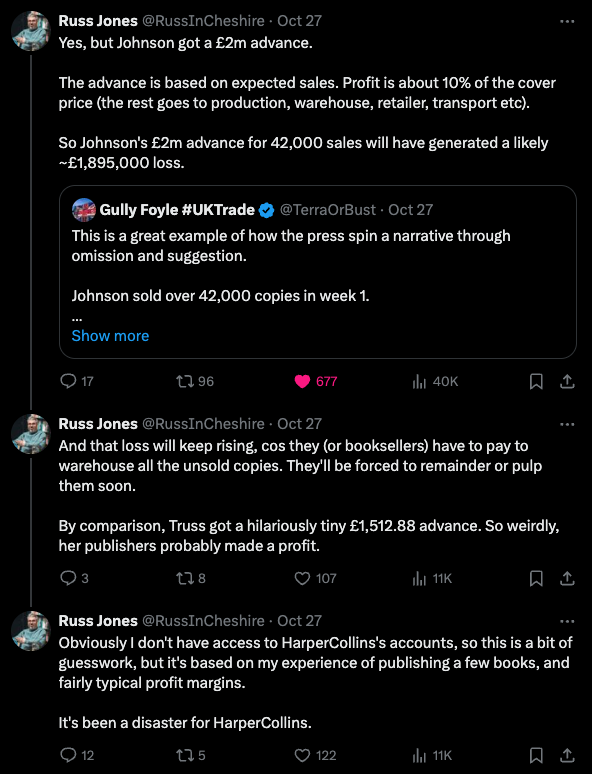

Rewinding a little bit. Is anyone still confused by the word recouped? For example, whilst writing this piece I discovered the disgraced former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson's new book very likely has not yet recouped:

It’s worth noting that, in most cases, unlike a bank loan, a record label advance isn’t a debt the artist must repay if the music doesn’t make a profit; the risk is the label’s to bear when bidding to sign and invest in the artist. If and when an artist does break even, they begin receiving regular royalties from their streaming income.

In some cases the label will own a record for 25 years and some deals with huge advances are even signed “in perpetuity.” That’s another can of worms for another time.

Cut To The Pub

Now, onto publishing, which came from the sheet music industry. It covers the lyrics and composition - that is, the “song” itself, rather than a studio recording of the song (hopefully Taylor Swift has clarified this in the minds of most people). Publishing works somewhat like an author being paid for the film adaptation of their book but they don’t need to direct the film or act out all the roles to get paid.

Often, the songwriter and lyricist are the artist, but there may be co-writers, meaning any publishing related income from the song is split among them.

For example, when a song like 'Somewhere Only We Know' by Keane is covered, licensed (say for a John Lewis advert), or played publicly, Keane earns money. Or rather, the owner of Keane’s publishing rights does. Which to extend the book analogy would be a bit like Shakespeare getting paid a cut every time someone puts on one of his plays.

Much like a record label, a music publisher provides an advance against future earnings to the songwriter(s) and lyricist(s), then collects money from various sources, including performances, cover versions, radio play, background music, a small percentage of each stream (see below), and synchronization licenses for ads, TV, and films. Publishers negotiate deals, track uses and collect income for the compositions they own (usually from the local royalty collection societies). Once the publishing advance is fully recouped, the artist may renegotiate against predicted future earnings or begin receiving royalties directly.

A quick note: Not all deals are the same; some artists self-administer or sign publishing deals without an advance.

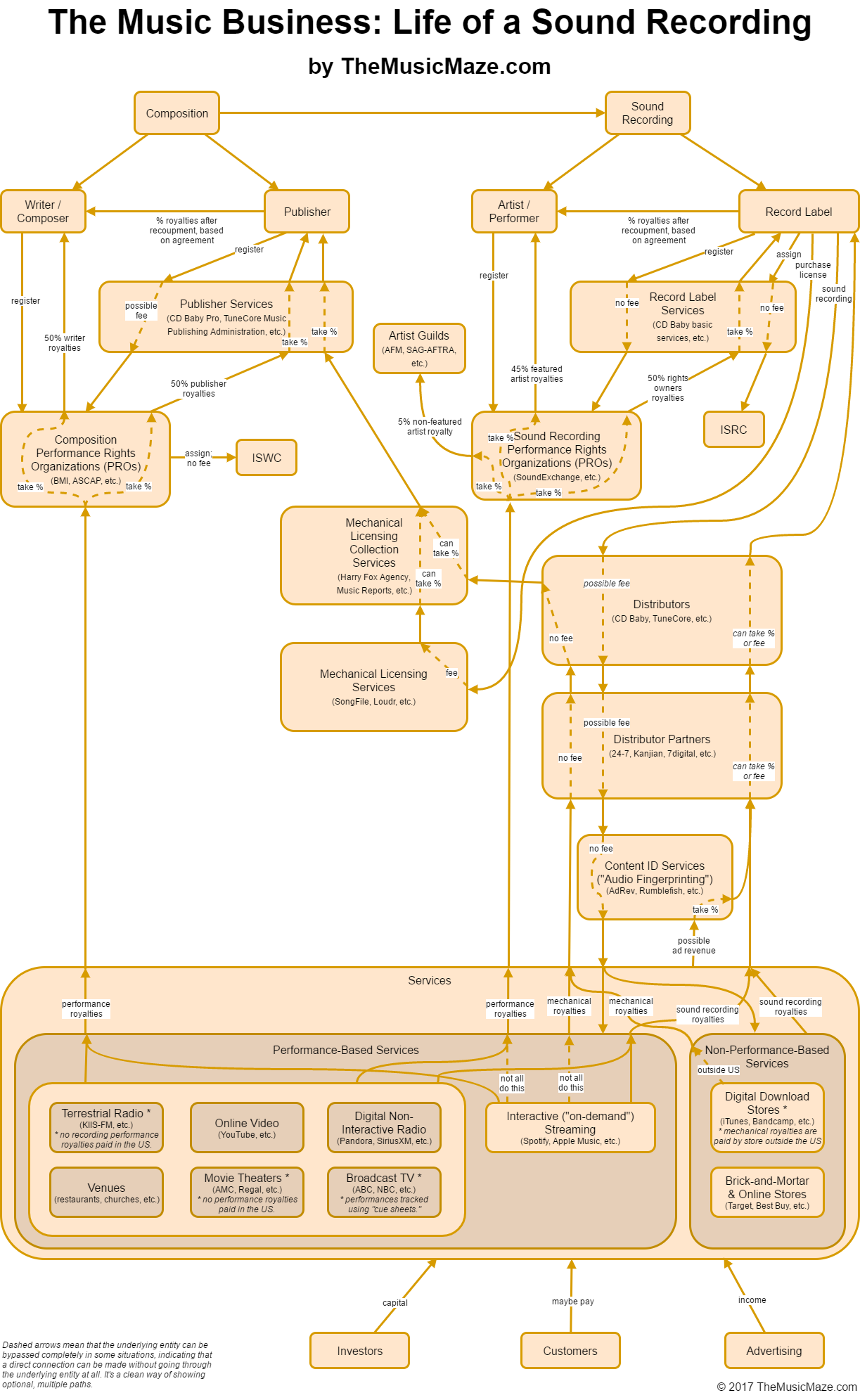

Confused? Here's a ridiculously complex infographic about how the US music industry "functions". To be fair, I don't blame anyone for not understanding how it works.

(see an explainer of this image, here)

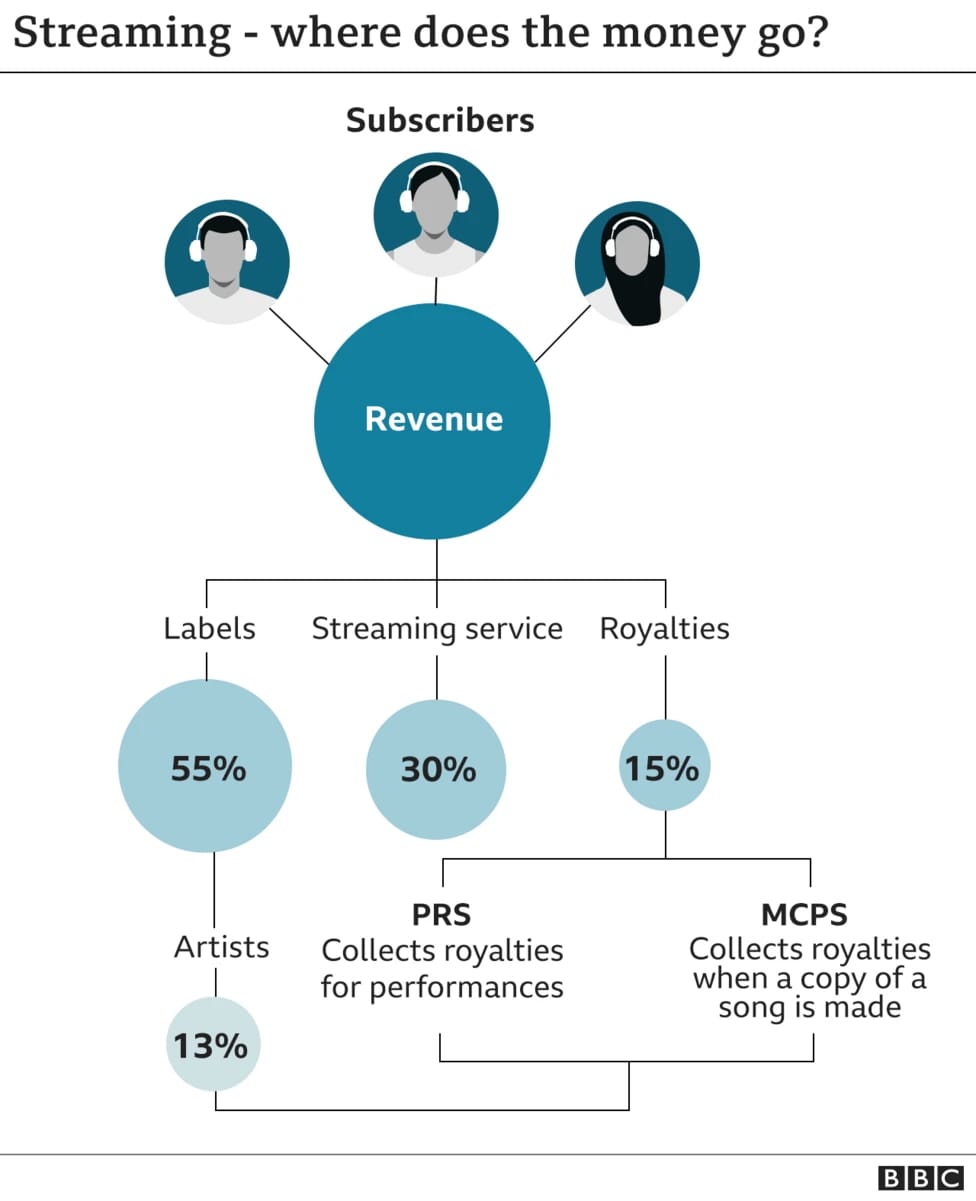

And whilst we're looking at infographics, here is roughly how the streaming pie is sliced in the UK (source: BBC):

Is There Streaming Money Under the Lily pad?

Lily Allen's Spotify states that she currently has 7.4m monthly listeners. Some of these people will listen to one song once this month, others will stream 20 of her songs a day almost every day, so without an audit of the label and the numbers being publicly available, there's no real way of knowing how many streams she has and therefore how much income she's generating each month.

Streaming doesn’t technically work on a per stream rate, it’s more like all the subscription and advertising money goes into a pot, then is split by the percent of plays each act gets for that month (some of the links at the end of this piece delve into streaming royalties if you want to get your head around it).

In terms of streaming income, Spotify is just one platform, Allen may have the same or more listeners on YouTube and Apple Music, as well as on Deezer, Tidal, Soundcloud, iTunes, 7Digital, Beatport, Bleep, etc, etc. All of these platforms have slightly different models and different deals with different labels but let’s gloss over that for now.

Is the math mathing yet?

Lily signed a major label record deal and is likely to be on an 18-20% royalty rate. The streaming income will be slowly paying back her advances and costs for each album, at approximately £3000 per million streams (although remember likely only 18% of that revenue generated is going toward the debt). Which may sound like a lot, until you consider some of her music videos were rumoured to cost £50k to make and that was at the lower end of what major labels spent on videos at the time when MTV was still a thing and YouTube kicked off.

So to be clear, while streams may bring in cash flow, a small percent of that money first goes toward repaying the artist’s debt i.e. the advance and other recoupable costs. Only once these costs are “recouped” does an artist start seeing their portion as royalties.

Even after recouping, traditional major label deals often leave the artist with just a trickle of each stream.

Whereas on OF, Lily Allen is earning $10 from each of her 1000 subscribers (minus a transaction fee, annual discounts, and whatever cut the platform takes). The contrast is huge but that doesn’t seem to stop NFT loving tech bros posting for clicks n’ clout about how more artists should do it all themselves and cut out “the middleman” (hashtag, not all the intermediaries and people in the middle are evil, and many add a lot of skill, time and attention to help artists grow a fanbase and develop a career) (many managers and labels often work for years before seeing any commission or return on their investment).

Yes, the layers of complexity involved in artist compensation and funding the resource that most releases need is far more complex and less lucrative than charging fans for access to “feeties”. This is not just a music industry issue and we need to reset how we value creative work and compensate all types of "content" - from journalism to movies to art to Twitch streams - in an increasingly corporate platform-dominated world.

The music industry isn’t broken beyond repair, but without change, its future may be harder to rebuild. Rather than blaming "the middleman" or yelling at artists to do it all alone (that way lies burnout, potentially bankruptcy and only the rich making music) or ripping it all up to start again, we need to recognise the time and investment that goes into making music and getting it to you, the fan.

Hopefully, with a little bit more understanding and appreciation for the time and money required to release music, discussions like this one would be filled with ideas of how we - artists and fans alike - can unite to capsize the current model, dry it off, apply some SPF and - I can’t figure out how to keep this analogy going - upgrade to a system that's fairer and more transparent for everyone.

For starters, renegotiating pre-streaming record deals and a new streaming royalty model, now that would truly make many in the industry smi-iiiii-ile.

FURTHER EXPLORATION

Courtney Love Does The Math - breaking down a million dollar deal (Salon, 2000)

The Pop Craveification of Breaking News (Taylor Lorenz for User Mag, 2024)

More Perfect Union's response to Spotify founder Daniel Ek's comments about creating music being almost free, with lots of background on their business model:

This post is for paying subscribers only

Subscribe now and have access to all our stories, enjoy exclusive content and stay up to date with constant updates.